The West Coast World of Barry McGee

Barry McGee converges graffiti and fine art on West 24th St.

A Barry McGee show is a multisensory, world-building experience. In the case of his exhibition Talk to Nature at Lehmann Maupin, that means bringing some west coast culture to New York — soft sad surf music playing on a repeat, huge colorful panels leaning on the floor, a chunky TV with snapshots of graffiti artists.

Born in San Francisco and part of the Mission School movement in the 90’s, Barry McGee is best known for his graffiti art and mural installations. There’s inevitable tension when trying to have a formal gallery exhibition of an artist originally known for street art, but in this case it works surprisingly well. The basement floor of the gallery turns into Barry’s world, rooted in a San Francisco DIY ethos and the city’s surf and skate culture, but with a sleeker New York element coming from the polished canvases hanging on the walls.

The show feels like a tribute to McGee’s interest in unusual combinations, both in the artwork itself and his creative partnerships. The show is hosted in combination with an Osgemeos show on the first floor, and a few works on both floors are collaborations between McGee and the famed Brazilian graffiti duo (the NYT referred to the artists as “aging taggers,” ha). McGee also gives up a half-wall of his own show to Bay Area artist Ryan Delaval as part of his commitment to keeping his shows as non-commercial as possible, according to a gallery assistant at Maupin. And it works — those combinations are partly why the show feels more authentic than other street artist exhibitions. Street art is always in conversation with other visuals; it’s not meant to be viewed on a white gallery wall. And in this case it also works because of the art itself, colorful and fun with a nod to those street-art roots, but ultimately heading in a direction that’s more formal and refined.

The first time I saw McGee’s work was at the Berkeley Art Museum in 2012, when my high school boyfriend enthusiastically brought me to his show (he liked skating and zines and things like that, which in the Bay Area means you probably like Barry McGee). I’d never heard of McGee, and in my 16-year-old earnestness I was mildly aghast at the giant red “SNITCH” spray painted on the outside walls of the institution. Turns out this wasn’t real spray paint — again, how do you exhibit a graffiti artist authentically at a museum? But regardless of how successful that effort was, inside was an experience that’s stuck in my head all these years. It was the first time I’d seen art that was so experiential and so much fun. I remember sitting inside of a reconstructed surf shack in the museum thinking “wait — this is allowed?” It was such an interesting, accessible experience, especially for a teenager, and it shifted my understanding of what an art exhibition could be.

There are no reconstructed surf shacks this time, and no falsely spray painted walls. But there are some really good artworks of the more traditional sort, with the same motifs that have jumped from sketchbooks and brick walls to canvases. Part of the fun of McGee is getting to know his themes — the drooping or snarling faces, his stylized typography, brightly-colored repeating patterns — and seeing them morph and combine throughout his work. “Combine” is a key word for this show. Many of the artworks are large, colorful canvas/panel combinations, using a combo of acrylic, gouache, and spray paint to combine his scowling heads with Ed Ruscha-like text and boundlessly repeating patterns. The result is a really cohesive body of work, where you can see McGee carefully testing different combinations of the color maroon, with frowning faces, with the number 100, and so on. It’s not always successful. Sometimes the canvases can feel random — but seen together they create a feeling of thoughtful experimentation, and prompt you to think about which combinations work and why.

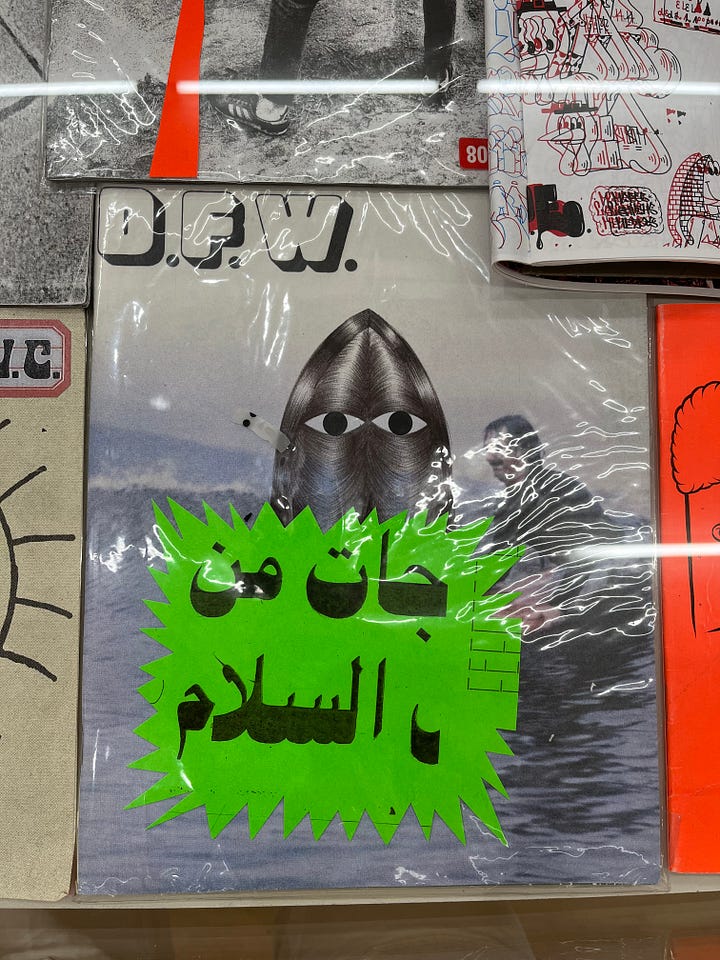

The paintings have an airbrushed precision about them. Influences from his wife, the painter Clare Rojas, seem clear, with her combination of organic shapes depicted with hard, clean lines. The lines can be so sharp, and the colors so bright, that it starts to feel overwhelming, and for those moments it’s a relief for the eye to see the few soft elements — a loose line of gray spray paint trailing across the canvas, or a giant circle of what appears to be tape or clay hanging next to a painting. Those elements connect the paintings to the zines and graffiti they grew out of, and I wish the gallery let you explore that connection more by flipping through the zines they’ve set up (a type of small-batch, non-commercial booklet). Instead, the zines are kept under glass, and you can only peer through it at the covers.

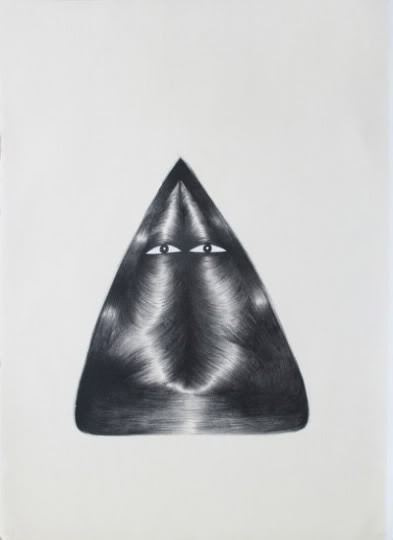

I also wish you were allowed to flip through the zines because that’s where McGee’s ballpoint pen drawings are, and I love his ballpoint pen drawings the most. They are an almost absurd elevation of this most ordinary tool, the ballpoint pen — each one a meditative, mesmerizing pattern of thin drawn lines that somehow create dramatic shading and volume in the sad, sagging faces McGee draws over and over. These drawings sum up what makes McGee so interesting, and what stuck with me from all those years ago in the Berkeley Art Museum. A drawing like that takes something ordinary and unremarkable, a cheap everyday object, and uses it to create something remarkable and unexpected. And isn’t that what the best art does — pushes you to see everyday things in a different light? The figure with the staring eyes on the cover below, for example, reads to me as an obsessive doodle of the kind you draw in school, but perfected and turned into something beautiful.

As for the combination artworks created with Osgemeos, I can’t really say these work well. Instead of bringing a new viewpoint, they feel haphazard: Osgemeos’s endearing kitschiness and particular color palette look confusing next to the precise lines of McGee. Those works show a successful collaboration isn’t just pulling two things together, but maybe that’s the point of new combinations — you test something out to see what works and what doesn’t. And in the end, it’s truly impressive to see two legends of graffiti art in the same place at the same time.