The Delightful, Shark-Infested Waters of Clare Rojas

A contemporary painter whose curious and compelling works explore the inner worlds of women in surreal and colorful lines.

I first encountered Clare Rojas’ work last year at Andrew Kreps gallery in Tribeca, and it stopped me in my tracks. Precise and technical lines, unusual pairings of flatness and texture, bold colors without garishness, and most of all, a quiet sense of the slightly menacing, awe-inspiring world around us (our inner world, outer world, both?). So I rushed to see Rojas’ latest show Clare’s Balls, running from April 25-June 1 at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco, where I was both enchanted and disappointed. Rojas’ unique approach, full of mystery, solitude, and nature, is present in many of the works, but some of her newer, more abstract works feel more like a formal exercise than a compelling painting.

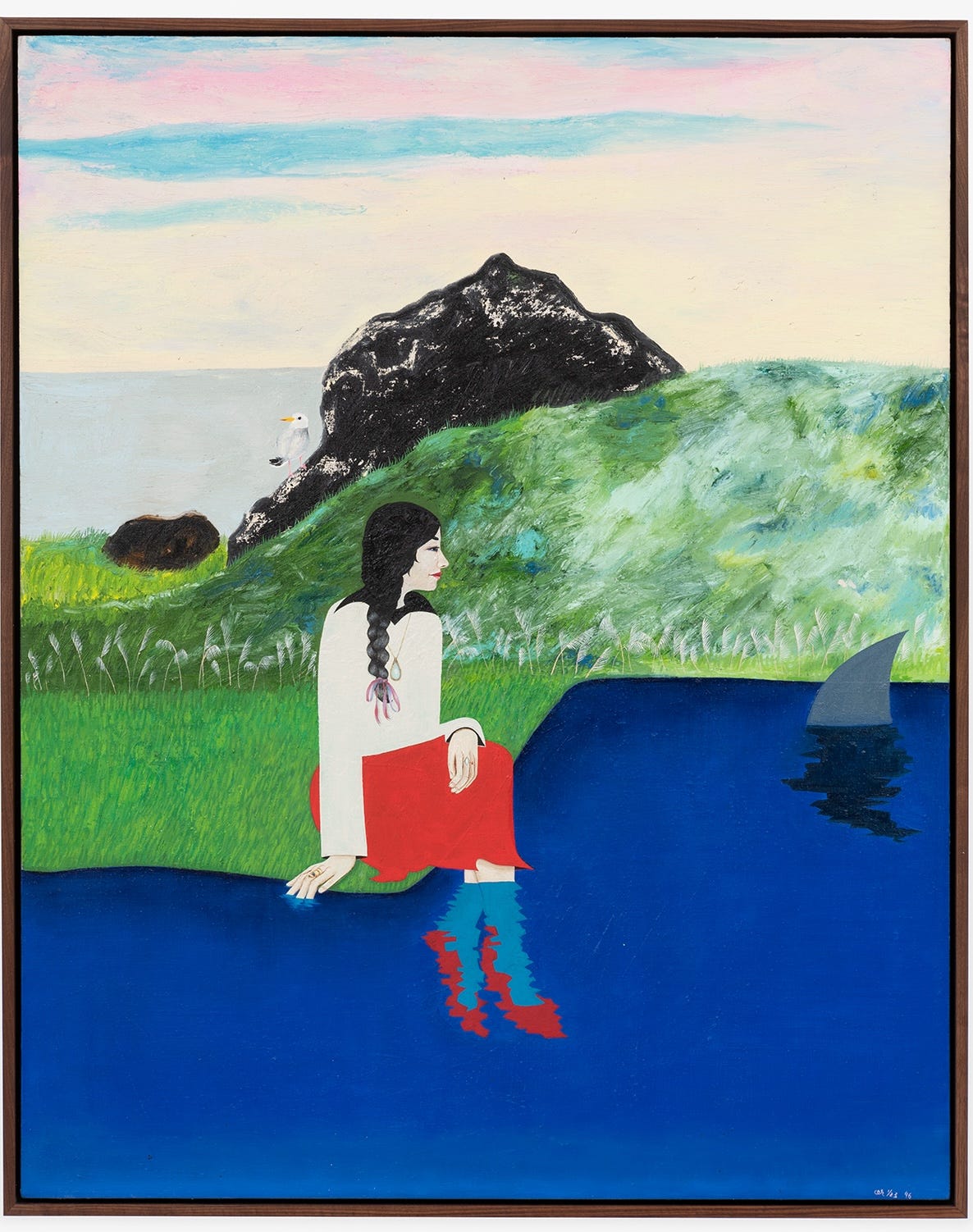

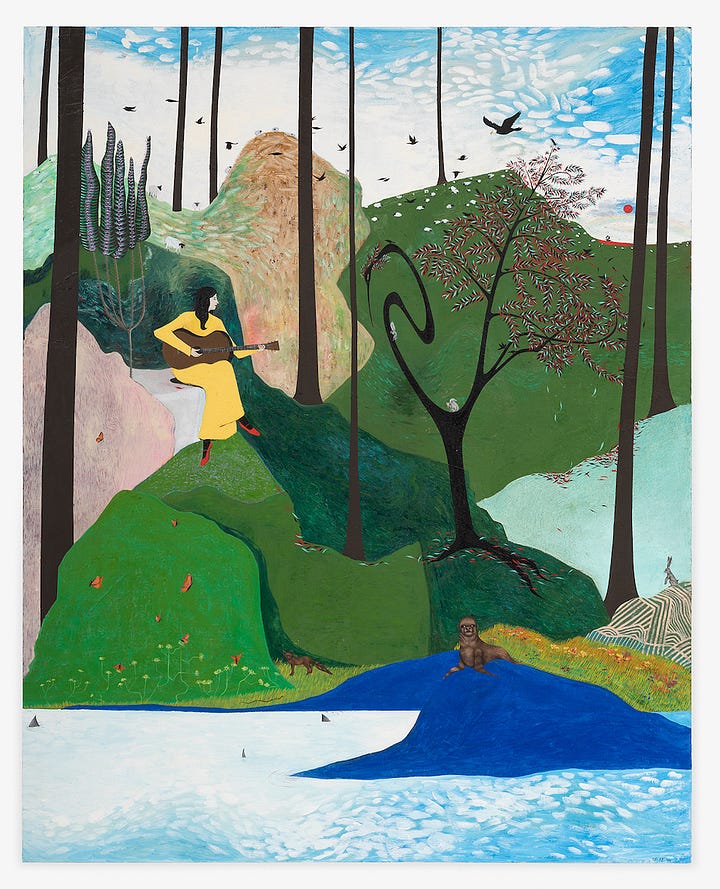

In both shows, Rojas paints women doing things — playing guitar, walking away, watching a shark approach, etc — always with a sense of stillness and calm. Her paintings feel like a curtain pulled back on inner life, marveling in the expansiveness of it and taking pleasure in being alone. Night Rocks (2024), for example, a new painting with a woman tiptoeing away on an orb into the night, feels like a mischievous peek into someone slipping away on their own adventure. Women are mostly alone in Rojas’ paintings, but often have silent company in the form of a creature, parallel and independent companions that often take the form of a sharp-beaked bird or almond-eyed dog. (Or in the case of The Stallion (2024), the creatures are an unnervingly realistic dead fly and a bird trapped in a picture frame. That’s also the only painting with a man in it. Do with that information what you will.) Along with animals, plants and the natural environment play an outsize role. The imposing natural backgrounds are part of what gives the works the feeling of exposing an “inner life;” the vast scenery mirrors the enormity of someone’s vast inner landscape. This sense of being connected to and dwarfed by the natural environment is part of what makes Rojas’ work so compelling, and why the newer abstract figures like Eclipsed (2024) feel colder and more isolated.

The natural setting also dryly points out humanity’s smallness compared to the enormity of nature (something that’s easy to feel if you’re among the huge coastal ridges and redwoods of Rojas’ local Marin County). The paintings imply a deep respect for the natural world. Trees battling each other with lives of their own, looming beach landscapes, and countless flowers coexist with the very dignified, slightly threatening birds appearing repeatedly times alongside rabbits, seals, and other mammals. It’s this coexistence that I miss in the newer abstract works — where are these slightly unnerving but somehow relatable pairings of human and animal?

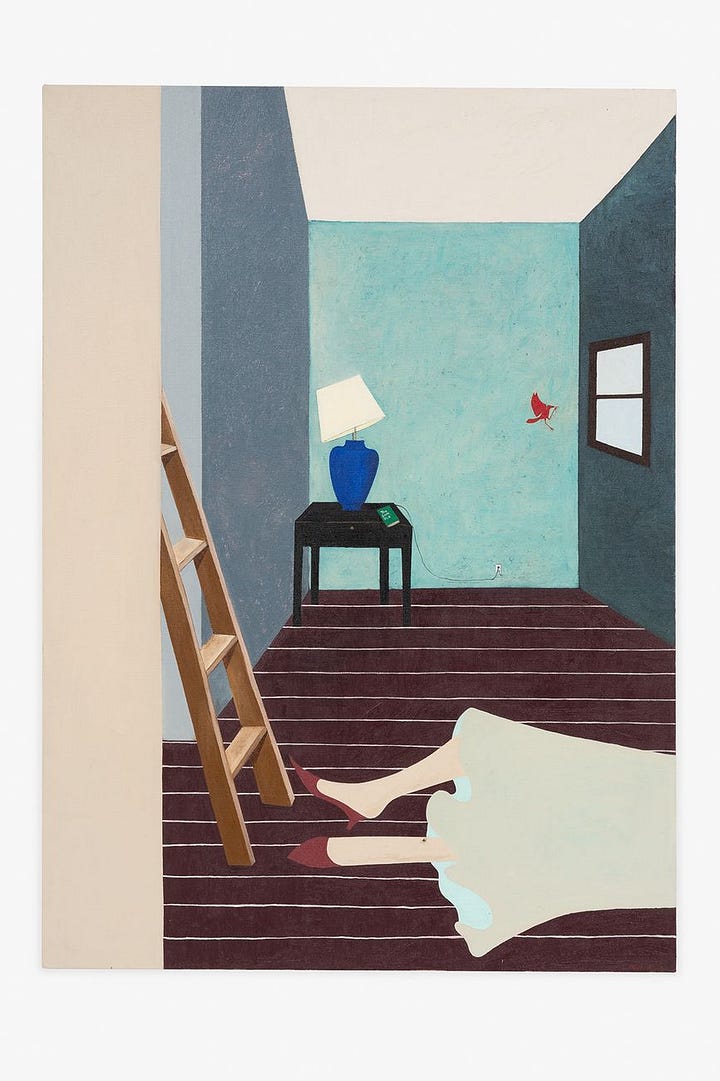

My favorite painting by Rojas is Sharks Point (2023), where a well-dressed woman peacefully watches a shark fin turn towards her as she dangles her feet in the water. What’s ordinarily a symbol of threat is apparently unremarkable, even expected. The woman’s red shoes are delightful, distorted by the water but somehow still having Rojas’ signature precision, while the hill behind her is gorgeously rendered with the texture of waving California grasses bent by the wind. A seagull turns a single beady, unbothered eye towards the viewer, and you’re left with the feeling that this woman with her shark knows something we do not. Maybe she’s just as dangerous as the shark. In contrast, interior scenes are openly bleak. Their tight, claustrophobic framing matches grim titles like It All Fell Down (2023) or They Were Both Stuck Inside (2023), which depicts the legs of a woman fallen from a ladder and a bird frantically trying to escape. In Rojas’ world, nature means freedom and peace while domesticity equals entrapment.

In the more recent show, Rojas also seems particularly interested in exploring contrasting textures and more abstract figures, which doesn’t always work. The contradiction between the richly swirling cloud next to a flat matte black one in Rain at Sea (2024), or the sophisticated shading in the landscape compared to the smooth red sun of On the Thirteenth Full Moon, She was Home (2024) are beautiful and intriguing, and I hope she keeps testing that path. But her abstracted figures composed of orbs and feet, like What Remains (2024) and Eclipsed (2024) lack the intimacy and appeal of her more traditional figures. Instead of the musings on nature and womanhood, with narrative clues and rich colors to draw you in, the abstracted paintings let you marvel at her technical skill but leave you emotionally cold.

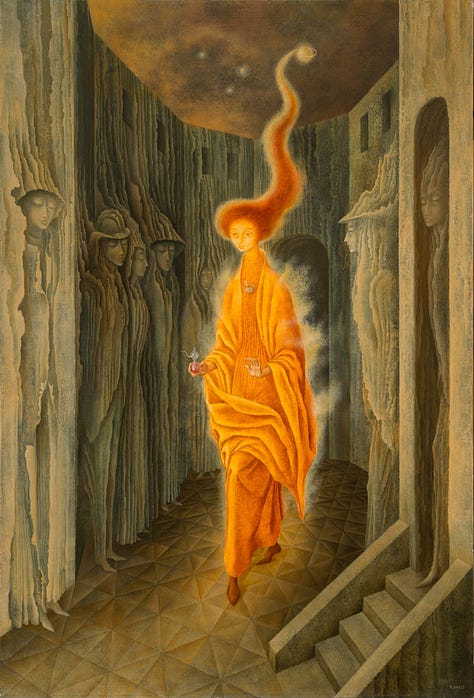

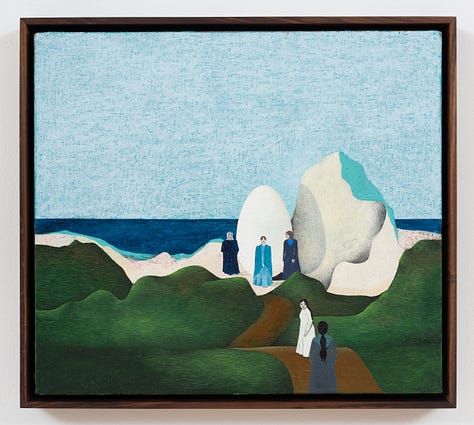

That level of technical skill is the common thread throughout both types of work, along with vaguely surreal imagery. With her sharp lines and clean colors, Rojas is a painter of precision, a hallmark of surrealist painters. The inevitable comparison is with Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, two wildly talented surrealists who became friends in Mexico City during WWII, both with a sly sense of humor and a strong interest in the occult, and whose paintings hint at the inner lives of women. Varo’s The Call (1961), for example, is another woman-figure on an ambiguous quest. This narrative curiosity shared by Rojas is both fun and enigmatic — paintings like Egg Rock (2024) or Full Moon Meeting at Glowing Tree (2023) gather small groups of women in mysterious circumstances, beckoning each other towards a giant egg on the beach, or pouring out a bottle of wine in front of a handful of broomsticks (are they items of domesticity or witchiness?).

Carrington’s Ulu’s Pants (1952) is another unusual gathering around an egg, and Darvault (1950) is another women-and-creature scene. But Rojas is more their extended cousin than a sister. Her work is smoother, quieter, and more modern than Varo and Carrington’s swirling candles, caged moons and horror-tinged creatures. There’s also a static, decorative quality to the works that’s nothing to do with the two surrealists. A pink striped skirt in What Remains (2024), or repeating flowers on the wallpaper of The Boot (2024) or The Stallion (2024) brings to mind the obsession with clothes and flowers found in Indian miniatures, in this case blown up and expanded into a western setting. These are traditionally feminine things, wallpaper and skirts, and Rojas’ preference for them reminds that she’s not rejecting femininity, but cagelike domesticity.

And now, when I take a long walk through the emotionally perilous streets of New York in something floral and pink or perhaps a feminine skirt, the thought occurs to me that maybe it’s me who’s the shark…

All images copyright of the artist and galleries. See more images with Jessica Silverman and Andrew Kreps.