Max Beckmann's Dark and Early Years

The Neue Galerie is showing some seriously bleak Germanic painting, and it feels more urgent than ever.

Max Beckmann (b. 1884, Leipzig, d. 1950 New York) was a chronicler of some of Europe’s darkest, war-torn years, and the Neue Galerie’s Max Beckmann: The Formative Years is not for the faint of heart.

The show focuses on the years between 1915 and 1925, passing from the peak of the Weimar republic to the brutal chaos of the post-war era. Series of society portraits like Elbset Götz (1924) give way to depictions of horrors in daily life, unnerving carnival scenes, and historical moments, along with a smattering of self portraits. Through the thick, fleshy individuals in his painting and the rabid, frenzied figures in his etchings, the uncertainty and sorrow of a war-torn society is plain — and all the more devastating to see with a war unfolding in front of us today.

The themes of violence and despair are not subtle. His famous series “Hell” depicts the violence and poverty of post-WWI life in Berlin in drypoint etching, the printed lines resembling frantic pencil scrawls squeezed onto the page. The figures pressed tightly against each other in a jumble of heads, hands, and noses are claustrophobic and disturbing, whether on a crowded street scene (The Street, 1919) or in discussion (The Ideologists, 1919). Drypoint etching uses acid, and there’s something apt about the thought of acid burning these images into existence.

This claustrophobic composition follows into his paintings. In Family Picture (1920), seven figures cram into the frame in what could be a cozy after-dinner family scene. Instead of domestic peace, anxiety radiates out from the figures, so close physically but making no eye contact, each lost in their own misery under the ghoulish light. Even when the topic sounds cheerful, as in the colorful Carnival (1920), the suffocating composition of the painting suggests there isn’t much comfort to be had even in life’s “fun” moments.

Beckmann was familiar with violence on a personal level. He volunteered as a medical orderly during WWI and had a nervous breakdown as a result, an experience that would shape his work for the rest of his life. The Nazis branded him a degenerate artist and he escaped to first Amsterdam, then New York, but his painting remained rooted in these years. Even the language he used to describe his art is violent. In his 1920 essay Creative Credo he describes the force of his motivation: “The stronger my determination grows to grasp the unutterable things of this world… the harder I try to capture the terrible, thrilling monster of life’s vitality and to confine it, to beat it down and to strangle it with crystal-clear, razor-sharp lines and planes.”

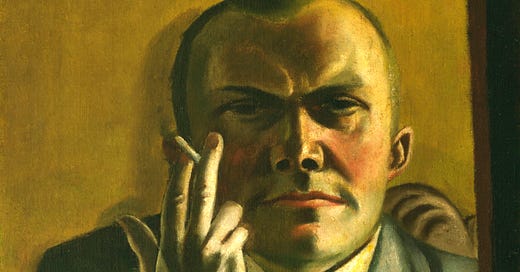

The best works — or maybe just the easiest ones to spend time with — are his self-portraits. He looks just the part. In a list of autobiographical facts he jotted down in 1924, he starts off with “Max Beckmann is not a nice man.” All it takes is a glance at his face to know this is most likely true. In Self-Portrait on Yellow Ground With Cigarette (1923) he stares out at the viewer with grim and knowing determination on his face — no self-deception here. Surrounded by his artworks, he appears both as a chronicler, someone rising above to document his surroundings, and as someone who’s also deep in the fray. It’s easy to picture him, with his meaty head and scowling face, as part of the mobs he depicts.

His woodcut portraits are also compelling, and are the only works that contain a rare sense of peace. A beautiful portrait of Marie Swarzenski shows his skill in shaping a face; just a few lines and shadows are all that’s needed to give her gravitas. Woodcuts were often used for illustrations in books — their clear, graphic quality makes them well suited to catch the eye and tell a story. In using them, Beckmann was part of a larger tradition of artists like Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Pechstein, and Ernst Kirchner. These were also popular at the time because they were cheaper to make and easier to sell than paintings, providing a much-needed source of income.

I think Beckmann’s best works — technically and emotionally — come come from later years (works like Death (1938) or Departure, Triptych (1935). For many of the works in this show, much of their interest stems from their role as historical objects. Some of the most gripping pieces function as portals that push you to learn about these fleeting figures and moments — like socialist leader Rosa Luxemburg, assassinated by the government, or Elsbet Götz, who was murdered in Auschwitz.

It’s not light stuff. But as a historical and graphic depiction of a place and time, and as a condemnation of the horrors of war — more urgent than ever — you’d be hard-pressed to find something better.

And if you’re anything like me, once you’ve seen the Beckmanns you’ll need to go downstairs for some soul-soothing Klimt landscapes.