Egon Schiele Never Gets Old

"Schiele: Living Landscapes" at the Neue Galerie is beautiful and worth a trip to NYC’s most disagreeable museum. The show runs from Oct 17, 2024 — Jan 13, 2025.

Egon Schiele: Living Landscapes at the Neue Galerie aims to elevate Schiele’s landscapes and cityscapes to the same level as his portraits: i.e. the thing he’s famous for. I don’t know how successful that effort is. There are almost as many portraits in the show as landscapes, and truthfully, if Schiele had only painted landscapes then you probably wouldn’t have heard of him. But the show is still a success, not only because a mediocre Schiele is still a Schiele, but because the show is not so much about the landscapes as it is a mini retrospective of one of the most profoundly impactful artists of the 20th century. It’s a rare chance to trace how his vision and visual philosophy is woven into every chapter of his career, and goes beyond just the sexy portraits he’s famous for.

Egon Schiele had a short and vivid life. He was born in 1890 in the town of Tulln, Austria, and died on Halloween during the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, three days after his pregnant wife died of the same illness. He was given to bold statements that ranged from the wildly arrogant (“I am everything at once”) to the glumly Germanic (“My essence, my putrescence”). His 28 years were spent in a frenzy of artmaking, which was most often portraits, most often erotically-charged (and uncomfortably, sometimes of his sisters); he’s also known for an episode of alleged child kidnapping combined with exposure to “indecent drawings” that landed him in jail. A friend I ran into at the show seemed positively guilty about being there at all given his background, an attitude I can’t say I agree with, but it’s true that his history sometimes supersedes his work. I imagine that’s why the Neue is trying to emphasize how his style also applied to less controversial topics like landscapes, and emphasize his quest to uncover the unity between nature, God, animals, and people.

In reality, the show is more about the artist than landscapes. There are almost as many portraits as land/cityscapes, as well as some archives, and through all of it you can trace an amazing consistency in Schiele’s vision. Even in his earliest works you see the color planes and sharp angles that are his hallmark style, with each work testing that visual language and pushing it a little further. His commitment to one style, regardless of whether he was painting lovers, friends, houses or sunflowers, paid off: at this point, Schiele’s forms are so familiar as to almost feel caricatured. With their elongated fingers, angular forms, and colors mostly in earth tones or red, it’s a distinct, slightly nightmarish vision of humanity and the trees and flowers that he believed were parables of human beings.

My favorite Schiele painting of all time is in the show, the showoffy Self Portrait in Peacock Waistcoat (1911). I like his saucy expression more than anything else: he looks like he knows all your secrets, and is judging you for them. Or maybe he’s judging you for not being as extraordinary a painter as he is. The whole work is richly textured and refined in a way that’s remarkable for watercolor and gouache, with layers of paint built up to shifting shadows and highlights that are both beautiful and technically hard to achieve. He’s even more playful with the colors than usual, with the blue in his hair or green on his face combining with the pattern on his waistcoat to create a feverish, kaleidoscopic feeling. In many ways it’s a classic Schiele portrait, with dark colors, long bony fingers, a direct gaze, and pops of red. But it’s unusual that he chose to include an actual landscape background with poppy flowers (instead of the usual figures floating in space), and that he’s wearing recognizable clothes (as opposed to being half-dressed or dramatically-robed). But again, more than anything else it’s the power of that expression that sticks with you, and maybe why this was the only decoration I had in my room for a long time. However else things were going for him, Egon of that moment was certainly pleased with himself — he’d created a little masterwork.

When you finally arrive at the landscapes, it’s true that some have a portrait-like intensity. In Town Among Greenery (1917), the town looks like a living creature in a stretched and compressed aerial view of Krumau, a precursor to Wayne Thiebaud’s dizzying San Francisco cityscapes. But more interesting than the full-fledged paintings like River Landscape with Two Trees (1913) or Yellow Town (1914) are the smaller architectural drawings Schiele made of his surroundings. With self-explanatory titles like Last Houses on the Edge of Town (1915), Supply Depot (1917), Farmhouse at Isel Mountain (1917), the building’s firm lines and empty windows read almost like historical documents with a glimpse into what the everyday world of pre-war Austria looked like: solid, immovable, a bit depressing. In Stefan Zweig’s memoir The World of Yesterday about pre-1939 Austria, he writes how Austrians of that era considered themselves to be part of a nearly 1,000 year old empire whose continued existence seemed as guaranteed as day following night (and oh, how wrong they were). I think a new edition of Yesterday illustrated by Schiele’s drawings is long overdue. Schiele didn’t live to see WWII, but you can’t help but wonder whether the stolid houses he drew are still there, or if they were destroyed like the rest of Zweig’s world.

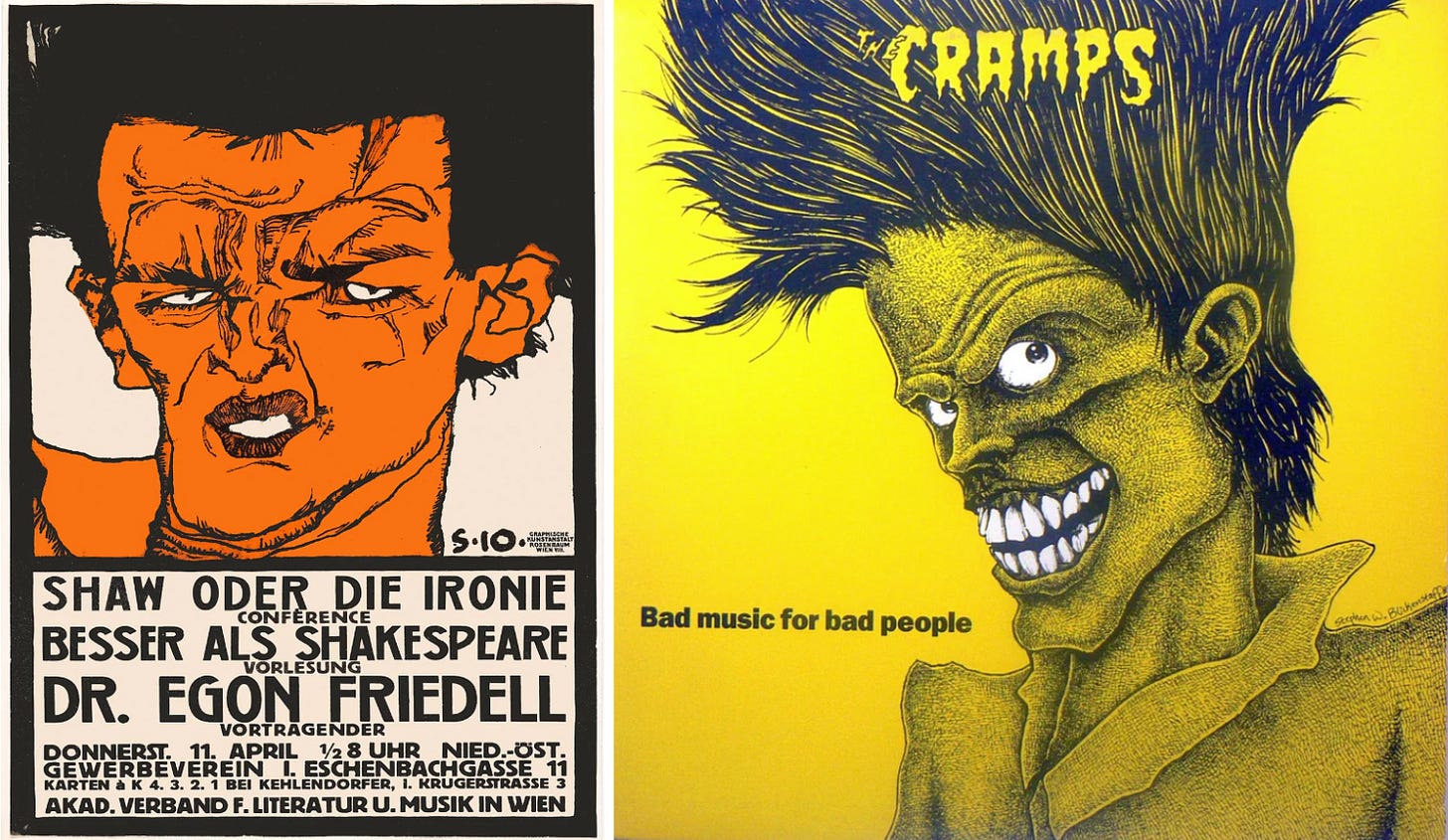

In the last room there are some archives, with photographs of the artist and a handful of sketches and posters. There’s almost a graphic design feeling to Schiele’s work, which comes out in elements like his boxy, stylized signature and works so well in poster format. I was obsessed with a seriously punk rock poster he made in 1912 for a history lecture: it made me think of the classic 1984 Cramps cover Bad Music For Bad People. Maybe The Cramps were Schiele fans?

Schiele has remained wildly popular for over a century now; his work clearly touches a nerve. It’s so specific in its style, yet also captures something universal about human suffering and love. His work is also wildly creative and unafraid of being strange or ugly, and spills over with a spirit of originality that still feels startling today.

As for the overall vibe of the Neue Galerie, it’s unpleasant as always. The museum guards are so stressed they seem to think the museum would be better off without any visitors, judging by the way they snarl at anyone who dares get too close to an artwork or tries to take a picture (one elderly gentleman was so startled he dropped the offending phone on the ground). So please enjoy this sneakily-snapped photo-of-a-photo — it’s not very good, but I risked life and limb (or at least my dignity) to get it.

All rights with the respective image holders.