The Allure of Sienese Saints and Cities

"Siena: The Rise of Painting" is one of the most intriguing shows I’ve seen at the Met in a long time, and left me with more questions than answers.

You’d think 700 year old religious paintings might not be exciting, but you’d be wrong — and if you don’t believe me, the crowds jostling to get a glimpse of gold crowns and pink robes would back me up.

The Rise of Painting is centered around a handful of artists working in Siena between 1300 and 1350, when most artistic production stopped as the plague wiped out 50% of the city’s population. Siena was at a crossroads of culture: not only a hub of the trade route between France, Naples, and Rome, but also the recipient of textiles from Iran and China. The works are spectacular, synthesizing these different influences into something stunningly beautiful, beguilingly modern, and quite weird.

The key works are two large altarpieces, made up of narrative panels depicting the story of Christ. Each panel is a detailed, strange little piece of storytelling. In one, a man holds his nose next to a skeptical-looking, apparently smelly Lazarus who’s been freshly unearthed. In another, a serving boy fills a stylish black-and-white jug to pour at the last supper, laid out on a delicately-patterned tablecloth. The curators argue that the obsessively-depicted details in the paintings offer an entry point for worshippers to feel connected to Christ’s story. If you recognize reality in earthly minutia like drapery knots or a bad smell, the thinking goes, you’re more likely to recognize the spiritual truth in the rest of Christ’s story — never mind the gold skies in the background of the paintings, of course.

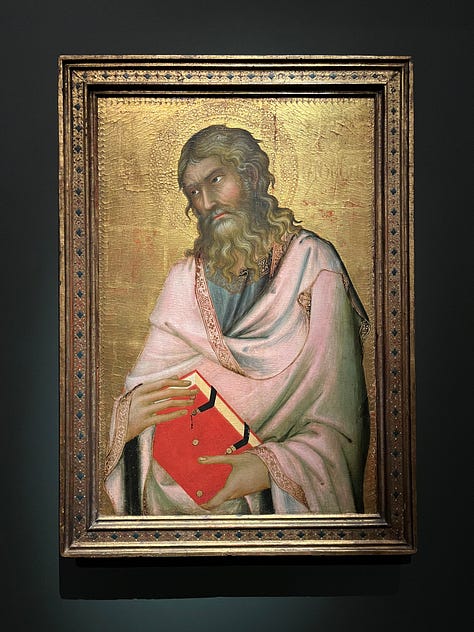

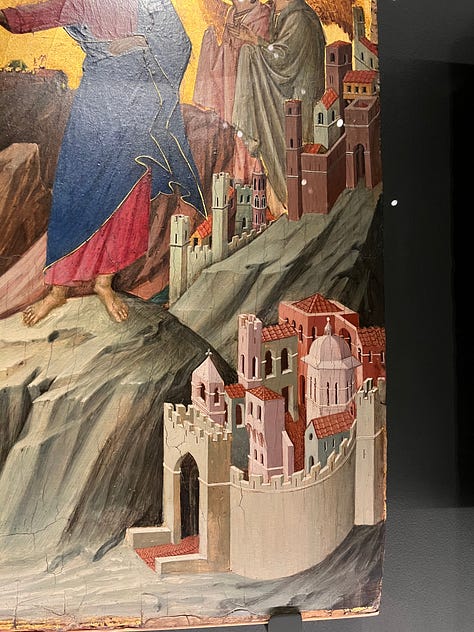

It’s hard to believe that this fanciful, jewel-colored world was easy to relate to, even with recognizable details. Each work is brightly colored and heavily stylized. Naturalism hadn’t come around yet in the early 1300s, and the figures are frozen in space with questionable proportions and stilted poses; they feel as inorganic as the clothes they wear or the sharply-defined architecture around them. This stiffness makes all those Jesuses and saints feel like expedients for the clothing and architecture — which, without the spiritual aspect, is where the real pleasure of the show is to be found (and I wonder if that’s where the real pleasure was found in the 14th century, too).

The colors are deep and luxurious, hardly an earth tone in sight: scowling saints in pink robes, Christ draped in rich red and gold, the Virgin reclining in a lapis robe with gilt trimming. The opulence of the clothing is underscored by the soft draping and delicate shadows, which draws attention to all the possibilities of that particular orange or teal. But the color that stands out again and again is pink. Raspberry, rose, flesh-toned, peachy, icy frosting, neon — all the hues you can think of. The medieval love of pink is something I’ve wondered about for years without ever finding a satisfying answer, so if anyone knows where I can find more on this, please tell me! And not just in the clothing, but in the buildings, archways, and church floors, too.

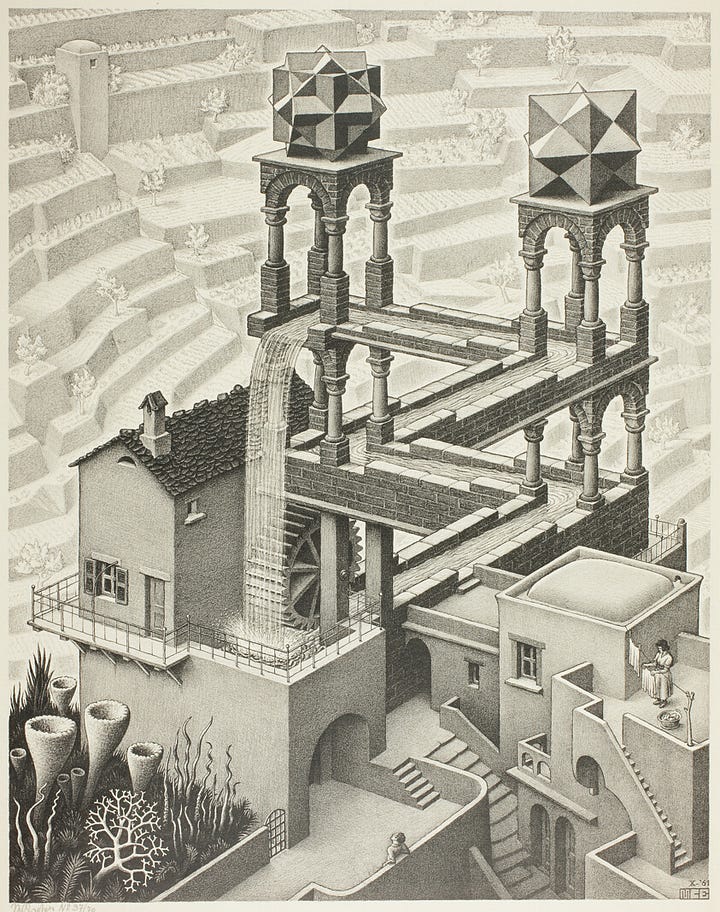

The architecture of these paintings is another marvel. The buildings are incredibly precise — arches, tiled floors, and columns that place the figures in a specific location, an exact church or garden. They are heavenly by virtue of their divine inhabitants, but also rooted in human civilization. And then there are entire cities painted in miniature, their sharp, clean lines depicting buttresses, tiled roofs and arched entryways. There’s something surreal and modern about them; it’s easy to imagine Dali delighting in their detail and their absurd juxtaposition next to a Jesus who’s twice as big as the town. The dizzying angles, staircases, and archways in works like Duccio’s altarpiece bring to mind M.C. Escher’s detailed architectural artworks like Relativity (1953) or Waterfall (1961). It turns out that Escher did spend twelve years in Siena, creating his own woodcuts of the city’s architecture and regularly exploring the city’s religious paintings. I’m surprised the curators didn’t draw attention to connections like this more; the throughline of these paintings throughout history better supports the exhibition’s claim that this era led to “The Rise of Painting.”

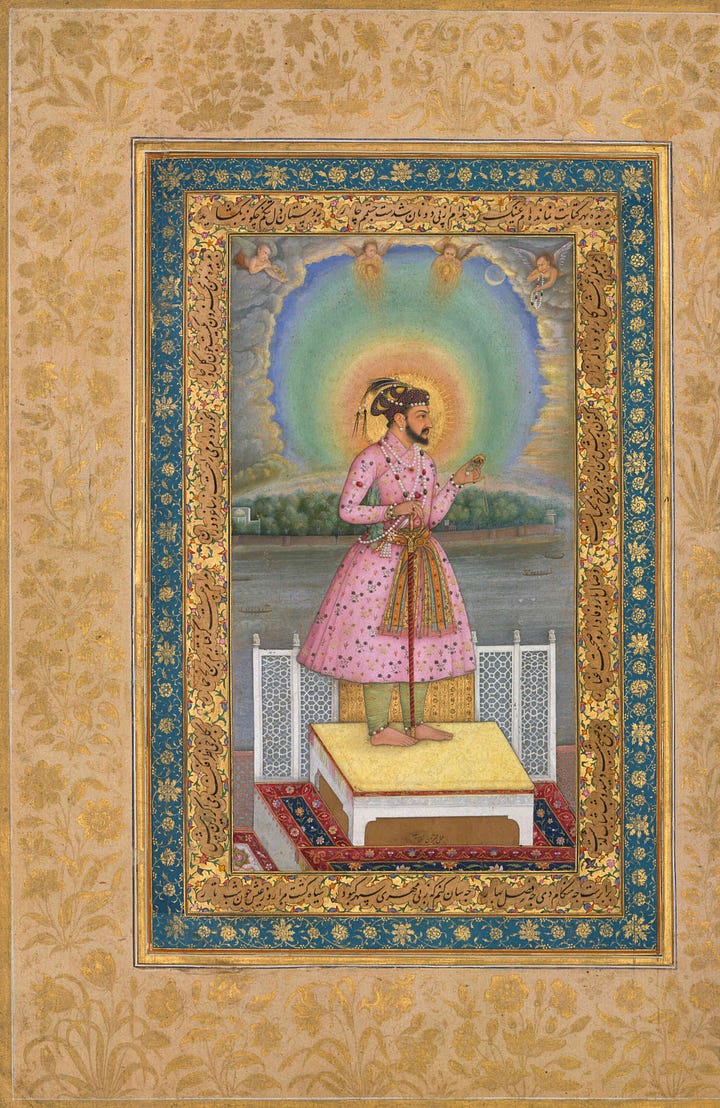

The show positions Siena as a crossroads of culture, but only touches on the artistic exchange with France and limits the connection to Iran to the country’s textiles. What about a more creative exchange? Siena’s obsession with clothing, architecture, and color, the focus on stylized figures with a disregard for natural proportions, and a penchant for pink — all bring to mind Mughal miniature painting. The Mughal miniature tradition, which originated from 16th century Persian (Iranian) rulers in India, is the only other place I’ve seen this much attention paid to clothes and the built environment, along with an emphasis on color, pattern, and precision. The show already establishes the commercial exchange between Iran and Siena — did Sienese painting and Persian art also share a mutual influence?

The show’s run at the Met ended in January, but it’s opening at London’s National Gallery in a few short weeks on March 7. If you find yourself across the pond before it closes on June 22, you know what to do…