A Giant Collection of Giant Artworks

"Giants" at the Brooklyn Museum, drawn from Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz' collection, is a gorgeous but somewhat random gathering of Black portraiture.

Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys, an exhibition of the couple’s private collection, is aptly named. Most of the works are literally gigantic, and the artist list reads like a Who’s Who of Black artists. An absurdly large Kehinde Wiley, two behemoth Amy Sheralds, an enormous Jordan Casteel — the list goes on and on with Mickalene Thomas, Gordon Parks, Nick Cave, Barkley Hendricks, Ernie Barnes, many more. It’s a must-see — but only because the works themselves are powerful. The curation and context from the museum leaves a lot to be desired.

The subtitle of the show really should be Contemporary Black Portraiture; more than 2/3 of the works are of people, real or imagined. The exhibition feels like a showcase of the breadth of talent and style centered around portraiture in the Black community, and it feels like a missed opportunity by the museum not to engage more with why portraiture is such an essential subject for Black artists working today, particularly as the genre relates to elevating communities and giving visibility to lives otherwise ignored. Most of the artists in the show are contemporary, although a few are from earlier days — for example it’s a rare chance to see in person photography by Gordon Parks (1912-2006), the first Black staff photographer for Life Magazine.

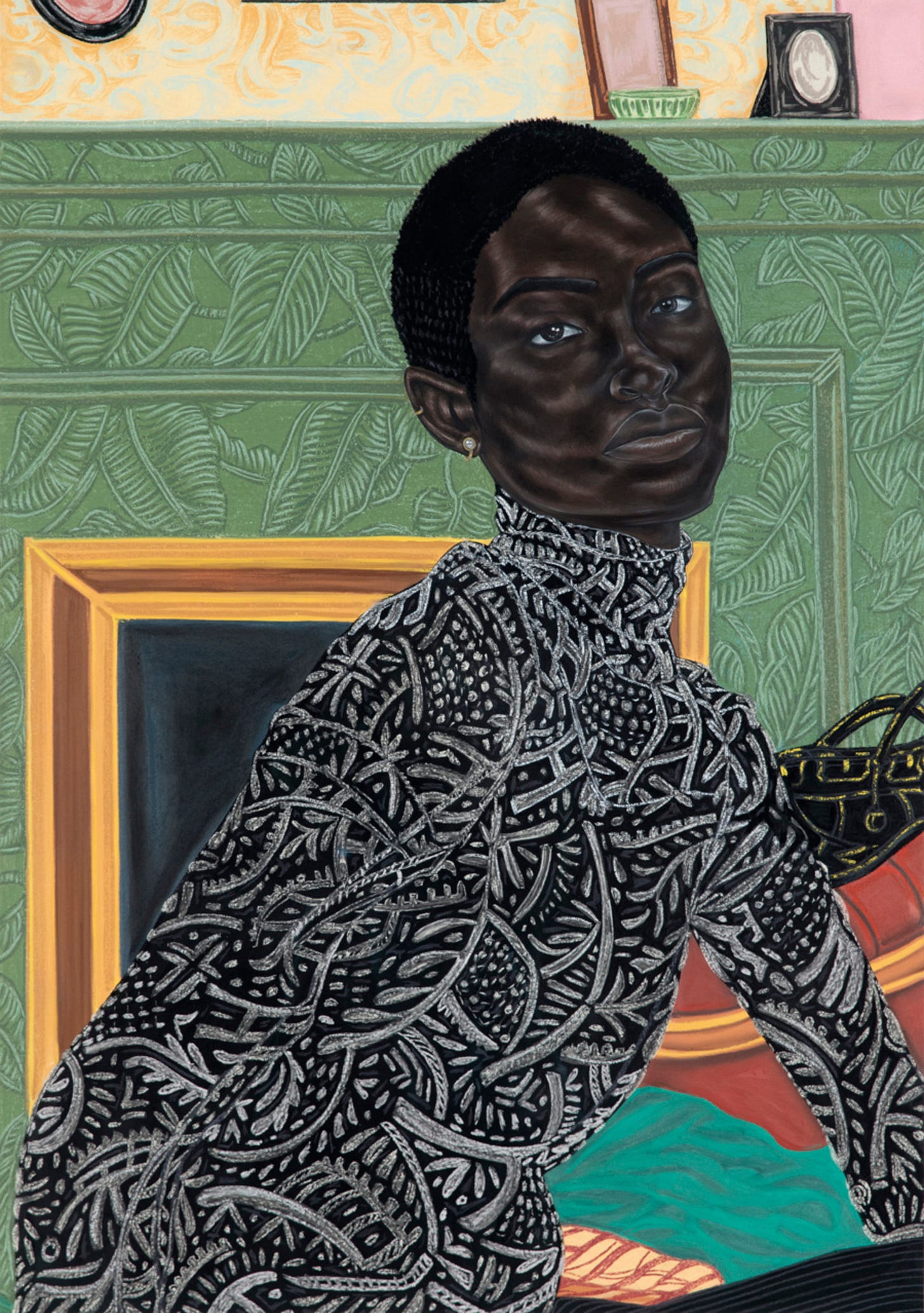

My favorite work in the show is a stunning drawing by Nigeria-born, NYC-based artist Toyin Ojih Odutola. The mesmerizing portrait Paris Apartment (2017) looks more like a painting than a drawing, and contrasts the elegant sitter’s delicately-shaded hair and skin with a flat, boldly-patterned shirt and similarly patterned background. It’s a prime example of the wave of extremely beautiful contemporary art coming from African and African-diaspora artists today. Odutola is in good company — artists like Amoako Boafo (born in Ghana), Wangechi Mutu (born in Kenya), Njideka Akunyili Crosby (born in Nigeria) are all masters of striking color combinations and compelling gazes. Their Black American peers, artists like Tschabalala Self and Henry Taylor (both represented in Giants), often work with a more straightforward color palette and are also drawing growing interest with their powerful portraits: Self hit a milestone in December with a Vogue cover of Nicki Minaj, and Taylor just closed an overdue retrospective at the Whitney in January.

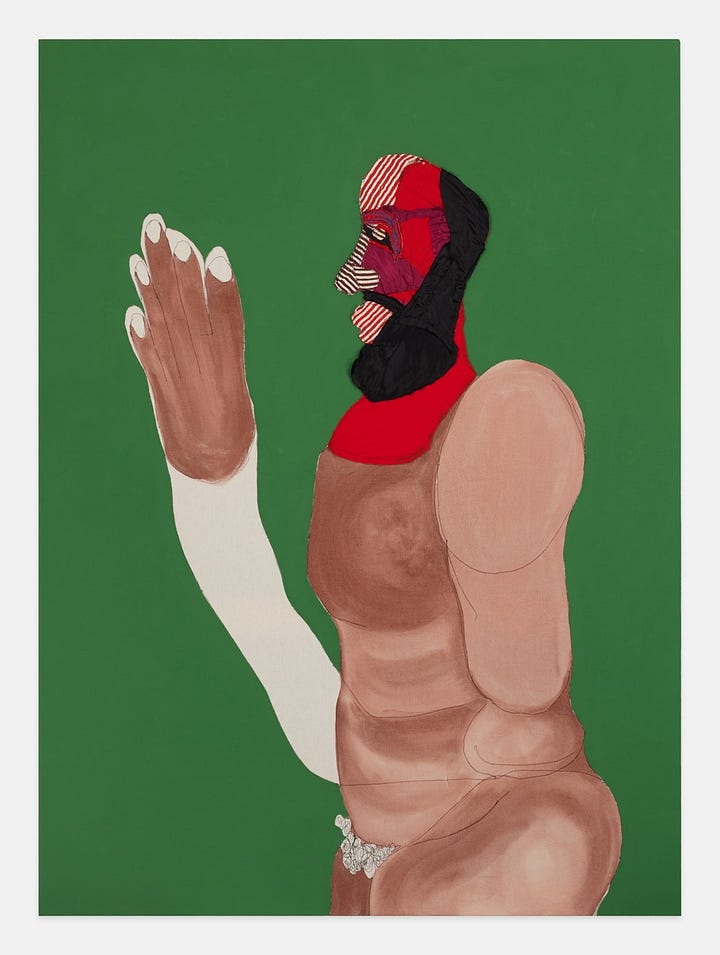

The works in this show are not only fascinating but also visually a ton of fun. The sheer size feels dramatic, and walking through room after room of vibrantly colorful, larger-than-life figures starts to feel like you’re surrounded by movie characters, some proud, some joyful, some quiet, most dressed in really excellent clothes. Standouts include a two-headed teenager hanging out in an eerie, peach-colored beachscape (Vaughn Spann’s Basking in the Wind, 2019), a glittery Nick Cave soundsuit, and of course a monumental pair of portraits by Kehinde Wiley of Keys and Dean.

Other than portraiture, though, it feels difficult to uncover the thematic connection between the works. The closest is relating to inequalities and identity — an entire room covered in mural-sized paintings by Meleko Mokgosi immerses you in daily life and power struggles in South Africa — but that’s of course a very different set of challenges than faced by the dancing figures in the next room by British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The saving grace, again, is the strength of the artworks themselves. A generous reading of the curation is that the thread winding its way through each of the works is the connection to and honoring of Black struggle around the world, but with an energy and dynamism that looks towards the future.

The show also prompts you to think about the role wealthy collectors play in the arts ecosystem. 20th-century collectors like Peggy Guggenheim, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller used their money, power, and taste to fundamentally shape our understanding of modern art. Founders of the Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum, and MoMA, respectively, they defined public perception of “good” art by influencing what was displayed and who was paid for it. Today, as Africa grows in global influence and the number of African artists on the fair-gallery circuit explodes, people like Alicia and Kasseem have the opportunity to define what we might come to think of as 21st century art. And that, maybe, is the throughline of each work in the show. Supporting the Brooklyn Museum with this exhibition firmly places the couple in the category of art world mover and shaker, and makes you wonder what’s next. The Dean Museum of Black Portraiture, perhaps?